The Reva Mann Story - Granddaughter of the 2nd Ashkenazi chief rabbi of the State of Israel

Between cocaine and commandments

By Dalia Karpel

Haaretz

So what if she's the granddaughter of the second Ashkenazi chief rabbi of the State of Israel? Maybe just for that reason she rushed to have sexual relations at the age of 15, on the floor of the synagogue in London, of all places, where her father served as the rabbi? Today, at the age of 50, Reva Mann is convinced that the reason for her journey of self-destruction was that she was lonely and miserable. Lonely and miserable enough to produce an autobiographical novel full of good and bad deeds - about doing it on your wedding night through a hole in a sheet, about the husband who runs to the rabbi with his wife's panties to receive the approval that she is indeed "kosher," and about why, in the name of God, he shouts "Gevalt!" even when he has it so good in bed.

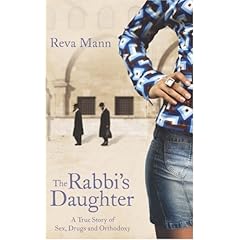

On Sunday in the wee hours of the morning, Reva Mann flew to London from Israel on the occasion of the recent publication of her book: "The Rabbi's Daughter: Sex, Drugs and Orthodoxy" (Hodder & Stoughton). A few hours before the flight she spoke excitedly about the busy week awaiting her in London: interviews for the British editions of Time and Elle magazines, as well as The Evening Standard, Sky News, the BBC, etc.

This week the book landed on the shelves of the bookstores. "The entire edition was almost sold out after the interview I gave to the The Sunday Times (London) supplement at the end of July," said Mann excitedly. "People bought copies by phone. The publisher has started to print a second edition."

Mann, a divorced mother of three, is enjoying this PR campaign: She was photographed twice for the article in The Sunday Times supplement: once disguised as a righteous ultra-Orthodox woman, and once wearing a suggestive outfit, sitting with her legs apart on a chair, with a glass of wine in her hand. It seems that from now on there is no more need to explain anything, and the book will sell itself. First in Britain, and soon in France and the United States as well. Mann, a person who was cured of her drug addiction and has become addicted to shopping, will be happy to pack her bags.

Unconditional love

Mann does not mention in her book the name of her famous grandfather, Isser Yehuda Unterman, because she worries that it will cause harm to her children. Her grandfather came to Israel from Liverpool and served as the chief rabbi of Tel Aviv before being appointed the Ashkenazi chief rabbi of Israel in 1964. He served in that senior position for 26 years, until his death in 1973.

Unterman is described in the book as having soft blue eyes, and wearing a silk robe during prayers in the synagogue. She says he loved her unconditionally - the opposite of her strict and restrained parents. Even when she did not demonstrate expert knowledge of religious texts, he was forgiving, and spoiled her. Every summer vacation, he visited her in her apartment in Rehavia, opposite the Heichal Shlomo synagogue in Jerusalem.

From the mid-1980s Mann has been living in a house in the German Colony, purchased for her by her late father Morris Unterman, rabbi of the West End Marble Arch Synagogue in London. He also left her an inheritance on which she is living. In recent years she has been writing a kind of personal column for two Jewish newspapers: The London Jewish News and the Boston Jewish Advocate. She dreams of a literary career and is now writing her second book, a comedy on the End of Days - "fiction for a change, and not a book about myself," she says.

"The Rabbi's Daughter" took shape in her mind two months after her mother committed suicide in an old-age home in Jerusalem, in the summer of 2004. Mann contracted breast cancer at the time. "I underwent chemotherapy, it was hard, and I only wanted to return to life, but I didn't have anything to return to. Even though I had my three darling children who live with me in Jerusalem, cancer provokes the question: 'Why do I deserve this?' My oncologist told me that there is no proven reasons for cancer, but that didn't convince me, and I had to deal with the question of why I had fallen ill. I started to write my life story in order to understand what had happened. Writing was a kind of healing. Before this book I didn't write anything, and the moment I got started, writing became a challenge. I decided that I can write.

"I came to my writing teacher, Judy Labensohn, with 20 pages. I had no hair on my head and I was very weak from the radiation. Labensohn lives five minutes from my house and getting to her was like climbing the Everest. She marked all the pages in red. She simply erased almost everything. I was shocked, but I was happy because I knew that I was the outstanding pupil who had found a teacher."

A few months later Mann completed the first version of the book. She sent the draft to an agent in England who decided to represent her, and says he came back to her in two weeks with a contract from a British publisher and from Dial Press in America. For half a year she went over the manuscript with a literary editor from New York and prepared it for printing.

The result - how shall we put it? - shakes you up. The scene when she loses her virginity in the synagogue reaches its climax with a cry of pain on the royal-blue carpet, under the ner tamid (eternal light). Mann stands naked in front of the Holy Ark and shouts "Hallelujah!" She hears steps, and before she gets back into her dress, the doorman of the synagogue is standing in front of her and reprimanding her: "You'd better go home now." The doorman, a righteous person, never revealed her secret.

At the age of 16 she took LSD for the first time, and that same year she spent time on Hanukkah at the Western Wall with her grandfather, the chief rabbi. There is no drug that she didn't try, including heroin. It all began with diet pills that she stole from her mother, and continued with sex, drugs and rock 'n roll with Nick Morgan, a musician who shared an apartment with his friends in West Hampstead. There were no rules there, she writes, but there was plenty of free love: "I was cool and free enough to allow every strange hand to feel me up."

The others were at least five years older than she was, and she worshiped them. She smoked grass, sniffed cocaine and felt that she belonged - as if they were her real family. While she was engaging in casual sex, her parents thought she was spending time in a Jewish youth club. And still, she felt empty. Like a snake that had shed its skin. At least until the next one-night stand.

Today, says Mann, she is happy - in the middle of a literary orgasm. "I never dreamed that I would sell the book and it never entered my mind that The Sunday Times would devote eight pages to me. Until the book came out I had been sick, I had a difficult childhood and I never experienced success. I didn't allow myself to have dreams of this sort. The reactions to the book give me self-confidence. For many years I couldn't stand reality because of my childhood, because of my mother, who suffered from manic-depression as well as breast cancer, and my sister, who was severely retarded. I preferred not to feel anything and to sink into drugs.

"When I grew up I returned to the ultra-Orthodox world, with the same extremism I had devoted to drugs. The 'high' of prayer was like the 'high' of drugs. There was no difference. My goal in life was to get lost. After finishing the book, the chapter of my life called self-destruction was closed. Now I'm dealing with reality. I'm free of everything bad. Although I'm lonely, I'm proud that I've come a long way. My book can help anyone who has fallen into the abyss."

Traumatic event

Mann's grandfather, Isser Unterman, was discovered to be a genius in Torah study in his youth. He identified with the Hibat Zion (Love of Zion) movement, and joined the Mizrahi movement. In 1923 he became the rabbi of Liverpool and in 1946 he decided to immigrate to Israel. When he arrived in Tel Aviv he was received by a large group of notables. The ceremony at which he was made chief rabbi of the city was held in City Hall. He became chief Ashkenazi rabbi of Israel in 1964.

His son Morris was the only one of the rabbi's seven children who chose to remain in England. He met his wife Ruth, who came from a traditional family, in the synagogue. She was a native of Wales, a university graduate and a language teacher. The couple lived in London, and in 1952 their eldest daughter, who is called Michelle in the book, was born. There was a problem during her birth, and at the age of one year she was diagnosed as being severely disabled. Reva Unterman (she changed her name later) was born in March 1957 in Sussex. When she was a year old the family moved to London. When her sister turned 13 she was removed from the house and sent to an institution. Reva was eight at the time and remembers the event as being traumatic.

In her book Mann describes her father as an anxiety-ridden man who was dependent on her mother, who is described as being addicted to tranquilizers and amphetamines. "She was perfectly dressed and groomed," says Mann. "She had wonderful taste and was careful with every detail of her external appearance, but within a few minutes a change would take place in her and suddenly she would collapse, crying, unable to function. My mother was a tough woman and I never felt self-confidence in her presence. Only when I took drugs did I feel confidence.

"She suffered from depression because of my sister. The birth changed her and everything collapsed after my sister was diagnosed as disabled. My father was an anxious man and a hypochondriac. In my parents' home everything was done out of fear of the future. My father was a scholar and an admired rabbi whom everyone consulted, and when he stood on the dais in the synagogue and spoke or sang, he charmed everyone. In public my mother was funny and smart and charming, but at home everything would turn upside down and the tension was intolerable."

How do you explain this dichotomy?

Mann: "Life in London was a game, of which the expensive clothes, the jewelry and the manners of the wealthy were a part. I received the most aristocratic education in London. My parents were part of this idea of class. They loved me very much, but I felt lonely and lost."

Last week a friend of her father's wrote in The Jewish Chronicle, after reading the article about her book in The London Times, that Mann had violated the commandment "Honor thy father and thy mother" - a commandment that he believes remains in force even after their deaths. Mann is not ruffled. "He didn't read the book," she says. "And therefore he can't complain about me. Everything I wrote in the book is the honest truth."

Top schools

Mann's parents sent her to the top schools. Her father, she writes, was a progressive person, who knew how to appreciate art and science, and read philosophy and psychology books. She studied in a Jewish school in London until the age of 10. Later she studied at Sinai College, a Jewish boarding school outside the city, from which she was expelled after a month. Her father decided to give up on a Jewish education and sent her to Queen's College, a high school for the children of aristocrats and diplomats. But even at Queen's College, she felt like an outsider and returned to the role of the bad girl.

"My parents loved me, but they were busy with the congregation and with their social lives. They expected me to be part of their lives and not to want independence or to have thoughts and feelings of my own, God forbid. I was not suited to their lifestyle and I didn't become part of it," she recalls.

While continuing with her wild lifestyle, she fell ill with Type B hepatitis after having sexual relations with a drug addict. Her parents took care of her for two months and afterward sent her to Israel, to recover on a kibbutz. There, too, she didn't settle down and she got into trouble because of a soldier boyfriend, who was arrested with 10 kilograms of hashish and blamed her. Her parents posted bail and the lawyers and she returned home to England.

All this would still have been tolerable in the family, had it not been for a serious relationship she had with a young, non-Jewish boy from London named Chris, whom she met in a bar. He was a photographer who worked for the music magazine Melody Maker, and she followed him and began using cocaine again.

Mann was angry at her father, who would not accept "Jesus the Christian who saved her life" into the family, and therefore the couple were forced to go live in the London suburbs. Chris opened a new world of art and music to her: photo galleries in Soho, exhibitions by David Hockney - everything a Jewish girl needs.

They ran a business for old cameras, until one day Mann discovered that the apartment where they were living had been purchased by her father and registered in her name. Chris was angry that Mann's father, who wouldn't recognize him, was controlling their lives, and decided to leave. Mann is sure that that was a sign from heaven, from her grandfather, who wanted her to rediscover the Creator. That was when she decided to move to Israel.

She arrived in Jerusalem in 1979, at the age of 22. She lived in a rented apartment, completed her matriculation exams and went on to the Hebrew University, to the department of English literature. Two years later a friend from the Or Sameach Yeshiva invited her to hear a lecture by a rabbi given to people who were returning to religion. "There was something so spiritual and fascinating in his words, and mainly in contradiction to all the prohibitions I had always heard from my father. Only there did I understand that we have a Torah."

After that illuminating experience, she went to study at the Or Zion women's yeshiva in Jerusalem and studied there for two years. She attended the yeshiva because she knew that at the end of the road, a shidduch (match) was waiting for her.

"I knew that, but that's not why I went," she explains. "Those two years were the most enjoyable in my life. The studies were very powerful, and the rabbis and their wives were amazing people. The problem was that I took it to the extreme, as only I know how to do, because of my emotional problems, because I wanted once again to reach ecstasy as I had when I was younger."

In the book she tells the story of her shidduch. She was 25, at the mercy of the matchmaker, who investigated her past and sent newly religious people to her. There was one guy from Alabama, who used to tie up his legs at night so he wouldn't turn over and touch his sexual organ, and there was the homosexual diamond merchant. And then came the ba'al teshuva (a newly religious man), an American. Instead of an engagement ring he brought her a prayer book. At the end of the wedding night, a fire burned in her, but he preferred to immerse himself in the holy texts and only fulfilled his sexual obligations to her rarely, mainly when she was ovulating.

The couple had three children. He preferred not to come to the last birth. It was her father who encouraged her to have an abortion between the second and the third child, after she contracted German measles. "My father was a progressive person," Mann says. "He actually relied on the opinion of his own father, the chief rabbi, when deciding that a life-endangering pregnancy could be considered redifa [being pursued by an enemy]. Since [according to Jewish law] you are permitted to murder someone who is pursuing you, you can stop a pregnancy that threatens your life."

That was also the moment when she understood that the ultra-Orthodox world no longer suited her. Although she gave birth to their third child, a short time later she began to have an affair with a handyman. Her husband wanted out; after six years marriage, they divorced.

'I'll find someone'

The last stormy chapter in Mann's life was with a man nine years her junior, who is called Sam in the book. She met him in a bar in Jerusalem, when he was working as a researcher for documentary films. Their wild sex life stopped suddenly when she contracted breast cancer and began chemotherapy. Later Sam's brother was killed in a terror attack, and at the funeral she understood that their relationship had to end. Since then she has been alone, and finding serenity in her new mission, writing.

There are two types of men in your book, those whom one marries and those with whom it's good to go to bed. Once this division was acceptable among women in relation to men.

"Now I'm middle-aged, menopausal, and after chemotherapy, and with God's help, I'll find someone. Even though the men in the book seem rough, I never went out with a coarse man. It's true that Sam fantasized about the nurses in the oncology department, but he himself was gentle and warm. I no longer know what excites me."

It's no wonder, after everything you've been through. How religious are you at present?

"I'm as religious as I can be. When I entered the ultra-Orthodox world I observed mitzvot (Jewish commandments) without being aware of the relations between man and God. You have to build these relations. It's impossible to take everything upon yourself at once. Today I'm religious and I like to study Torah, but it's hard for me to observe all the commandments. I hope that in the future it will be possible to build that more solidly. It's true that I came from a religious home, but at the age of 14 I ate pork sausages. In my father's synagogue I never felt any spirituality. In London it was a materialistic life. I had sexual relations in my father's synagogue because it was a quiet and accessible place. I got into drugs because I was lost. I know people who were into drugs and that didn't prevent them from finishing university and having a career. My self-image was low."

Your book is full of explanations of religious laws, accepted forms of behavior and mitzvot, as though Jews were a lost and exotic tribe that nobody has ever heard of.

"I'm very happy and proud that The Sunday Times decided to add a box with a passage from the book that deals with the mikveh (ritual bath) and the laws of nida (marital relations during menstruation). We, the Jews, need better PR than what we have today in the world. It's important that people read about it and know that we are a holy and pure nation, to whom the issue of purity is important."

Are you joking?

"Not at all. I'm happy that I wrote about these halakhot in the book. I feel proud, like the rabbi's daughter. I feel that I brought the entire Torah into the book. In each and every chapter there is Torah and Midrash and Talmud, and our role as Jews is to be a light unto the nations. I feel that I really am my grandfather's granddaughter even though I have a past of sex and drugs. It doesn't matter. It's just the clothing. Here I'm my soul. The clothing is the body, and the clothing of the Torah is Jewish law, Talmud, Midrash and the secret that comes out. In other words, sex and drugs are the clothing that is easy to digest and that's why they're in the book."

So what are the goals of the book?

"A. Everything you always wanted to know about Judaism and were afraid to ask. B. I hope that the book will reach people who are self-destructive and will help them to rehabilitate their lives. That they will learn from me."

What do you regret?

"Nothing. I think that everything I went through has given me the strength to be what I am today."

5 Comments:

Interesting. Does anyone know if you can get teh book in the US?

This woman was seemingly not abused, so what is the point of promoting her book and disgusting biographical details?

This story is very similar to several other son's and daughter's of rabbis that I have spoken to over the last several years. Many are considered the "black sheep of the family" or being "troubled".

What we all need to be doing is asking do children of rabbis go off the derech (path)? Blaming the adult children doesn't solve the problem. Her book is only considered disgusting to those who refuse to fact the reality that as a community we all have deal with the issues.

All too often celebrities (rock stars, actors, and even orthodox rabbis) have such busy lives that they are not able to spend quality time their own children.

The children of these individuals often are forced with dealing with the fact that never know if they are being befriend by others because of who they are as a person or because of who they are related to (or a decedent of).

Rabbis often work with people of all backgrounds and unfortunately it can put their own children at risk of harm. There is also the issue of the number of people who come into the homes of celebrities. Does a rabbi have to do a criminal background check on guests prior to being invited? The problem with doing that is the fact that the majority of sex offenders have never been arrested let alone prosecuted or found guilty of a crime.

Do we blame those who go off the derech? Or do we look deeper into their lives to find out if they were abused or neglected or if it was something else?

We need to embrace those who are in pain and stop the blaming.

I think Vicky is going a little overboard here. While Untermann may have been abused or just short of it, how do we know in this case that her story is not the result of her own possible moral shortcomings or mental illness. I don't think we have to go out of our way to dig up every case that MIGHT be abuse related.

Even if she sinned as a result of neglect, must she trumpet the manner in which she stumbled with every detail about the bima of the shul and enjoying lesbian sex in a seminary?

I suspect that people that agree with Untermann's approach are coming more from not understanding or having a problem with Orthodoxy as a whole or are just yentas with a penchant for wanting to hear salicious stories.

What woman of worth (eshet chayil) would leave and neglect her children, have sexual relations within their hearing with her lover and generally watch them being unhappy and confused. A decent mother would put her children first not indulge in her own self pity and self indulgent perverted pursuits.

The fact that she felt neglected should have ensured that she did not neglect her own children and leave them with their own psychological problems.

What really disgusts me is that she is proud of herself. Her father and grandfather must be turning in their graves.

Post a Comment

<< Home